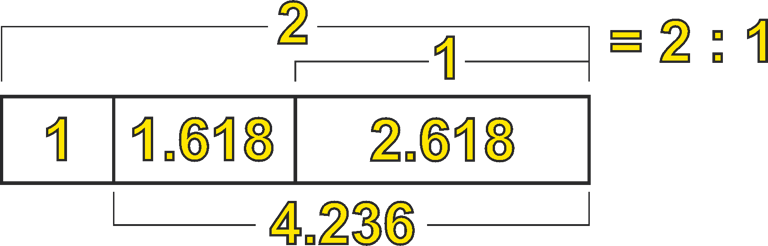

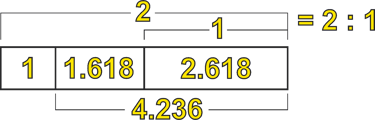

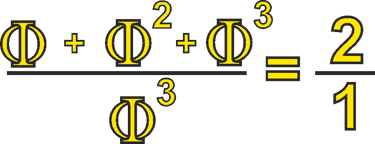

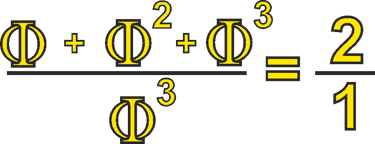

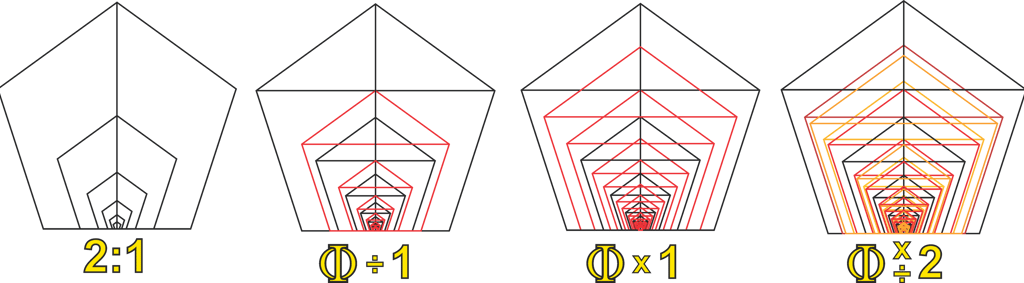

By definition, Phi is expressed as: the lesser is to the greater as the greater is to the whole, which also implies that the whole represents the next value in our sequence of Phi multiples. In this particular case, the greater is to the whole in the perfect ratio of 2:1 — the ratio of the octave.

By Cree M.J.

Phionic Geometry

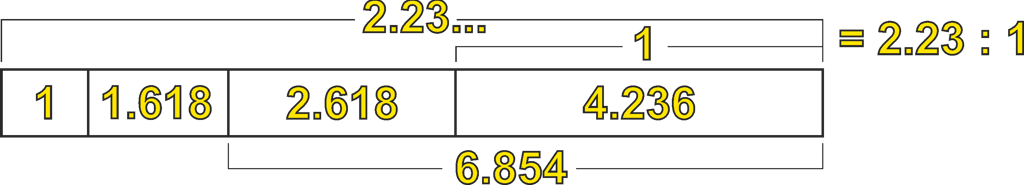

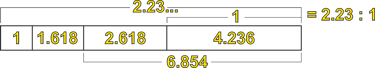

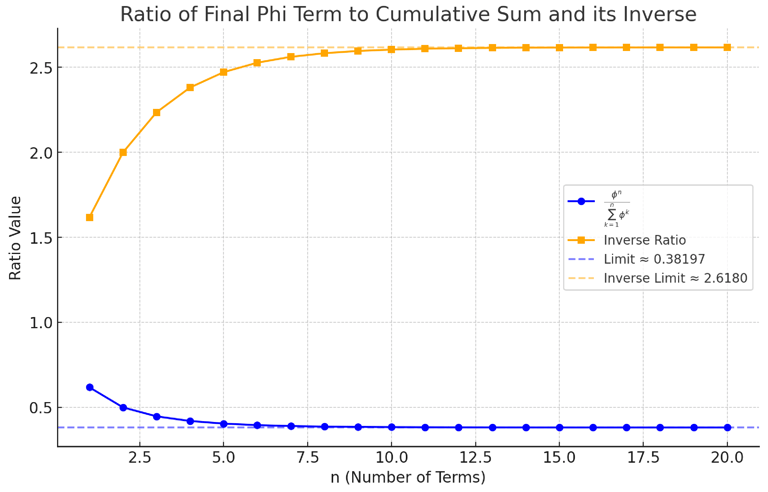

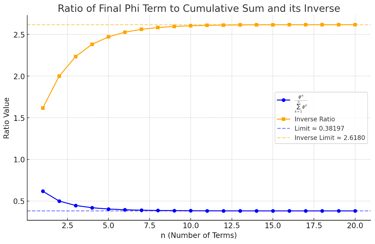

This is the only case in Phi where we find a perfect whole ratio, occurring between Φ³ and its cumulative whole. If we continue the sequence, comparing each progressively greater value to its whole, the ratios converge at approximately 1 : 2.618 (Φ²) or, inversely, 1 : 0.381… (the reciprocal of Φ²).

With this in mind, we can hypothesize that by imposing Phi ratios over a 2:1 octave framework, we continue to create intervals congruent with Phi and its exponential expressions, specifically Φ³ / (Φ¹ + Φ² + Φ³).

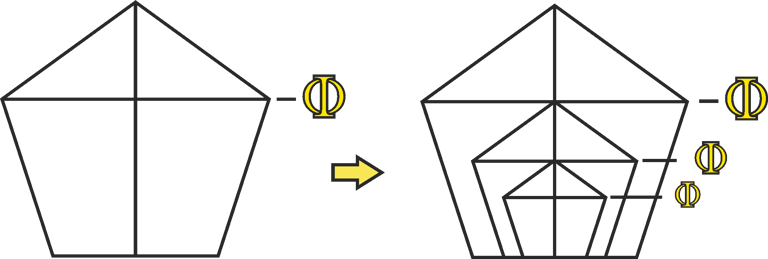

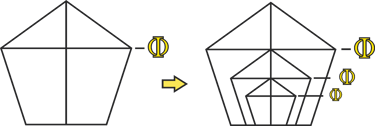

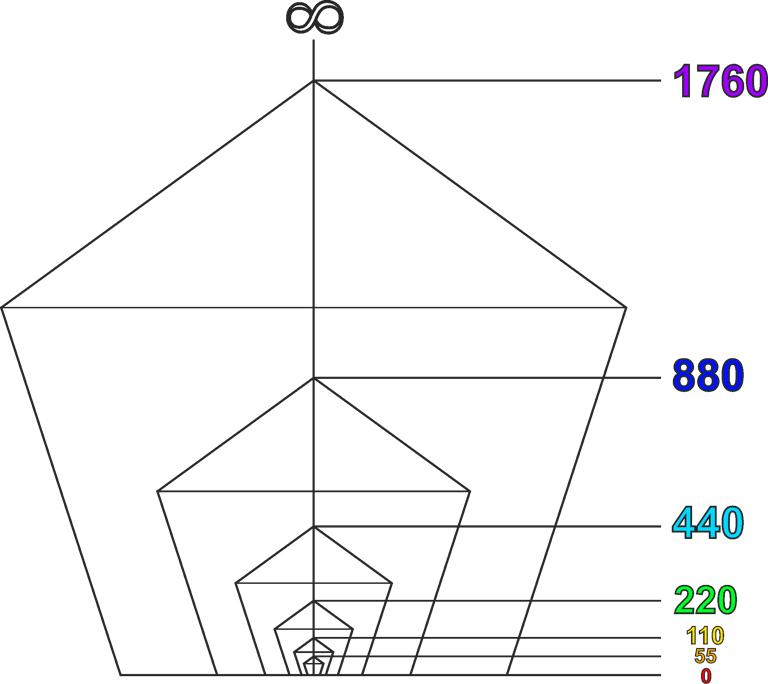

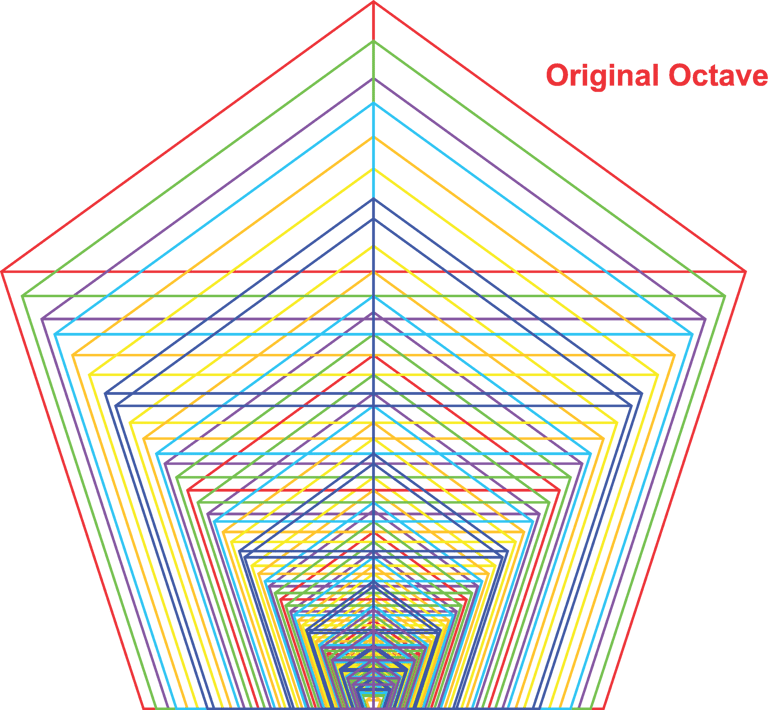

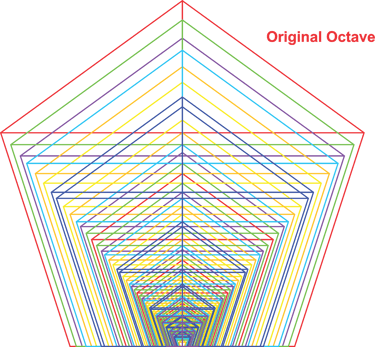

The inherent Phi geometries of the pentagon provide a useful visual guide for laying out Phi-related ratios within this structure. In particular, the distances between the apex, the base, and the midpoint between the outer vertices follow the 1:1.618 Phi ratio. By drawing lines along these points, we can use the pentagon as a visual reference for structuring and aligning Phi-based intervals.

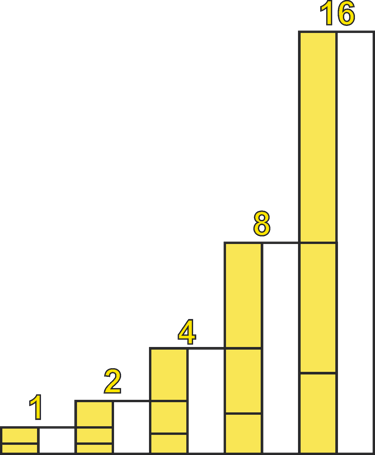

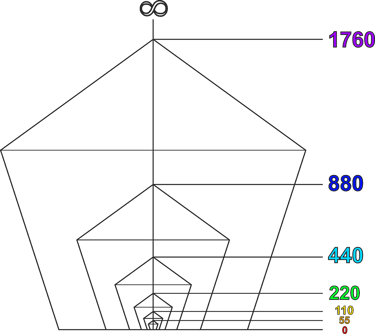

Let’s begin by establishing our first series of octaves. The exact values are arbitrary, but for the sake of comparison, we will assign the corresponding octave values from 12-tone equal temperament, with A = 440 Hz, as follows: 55, 110, 220, 440, 880, 1760 Hz, and so on.

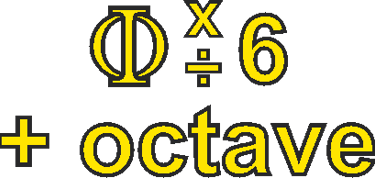

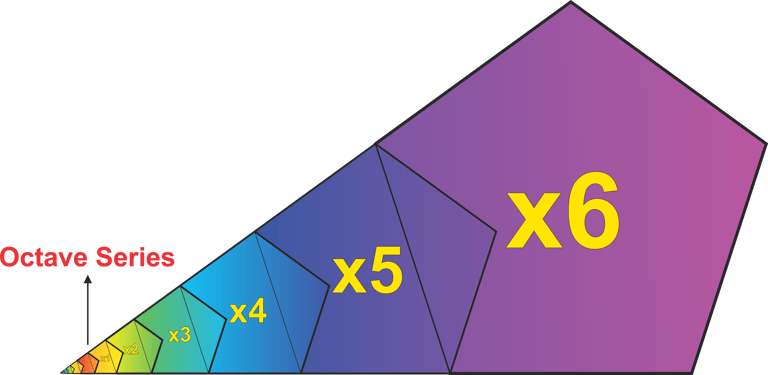

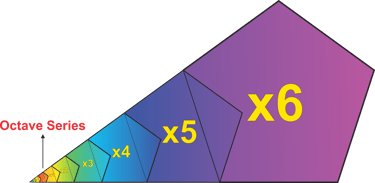

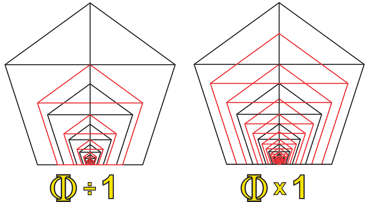

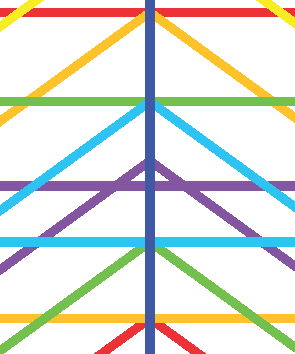

With the foundation established, we will next simultaneously multiply and divide each of our individual octave positions by Phi. To complete our first basic structure, we simply continue this sequence—multiplying and dividing by Phi from the original octave—and label each resulting value as either “Phi ×” or “Phi ÷” to indicate its position above or below the starting point.

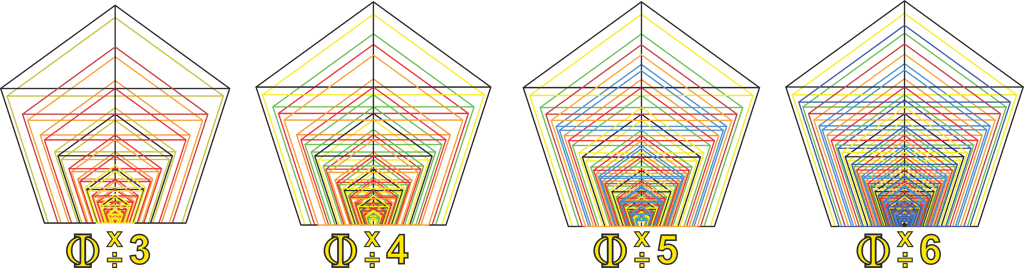

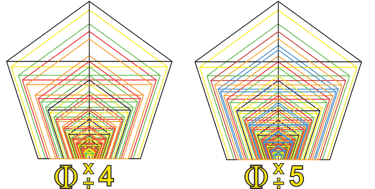

In this way, we generate Phi ×/÷ 1, Phi ×/÷ 2, Phi ×/÷ 3, Phi ×/÷ 4, Phi ×/÷ 5, and finally Phi ×/÷ 6 from each of our octave positions.

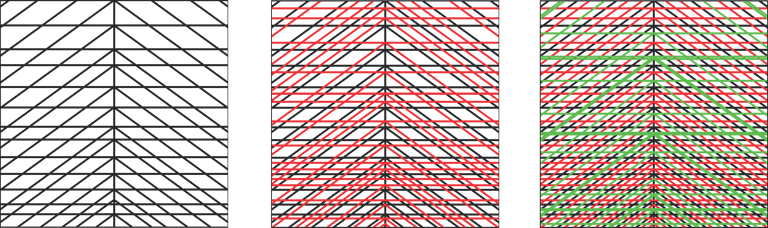

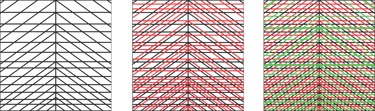

There are several points to note at this stage. First, we can see that our octave has been divided into 13 intervals—regularly spaced, yet unequal in size. Second, by observing the color coding of the different Phi series, we notice that overlapping intervals have formed a regular pattern, even though many individual Phi values extend from adjacent octaves. This is not yet our finished structure, but it helps to unpack exactly what is happening here.

If you pay close attention, you will notice that all of the geometric lines are aligned—except for the last series, Phi ×/÷ 6, which nearly complete the circle, almost meeting each other (Phi ×6 tip to Phi line of Phi ÷6 or Phi ÷7). Tracing back the sources of these Phi intervals, we find that this meeting point represents a convergence spanning 10 octaves and 13 individual steps—7 steps of Phi divisions and 6 steps of Phi multiplications. Note that the 7th Phi division is visually implied by the pentagonal Phi line of Phi ÷6, though we have not explicitly constructed that step yet.

If we were to create another pentagon at this Phi ÷6 line and compare its overall ratio with Phi +6, we obtain a ratio of approximately 1:1.01758…, which can also be expressed as Φ¹³/512, with 512 relating to our octaves as 1 doubled 10 times.

While Phi ×/÷ 6 (or 13 steps) might seem like an arbitrary point to define the structure, continuing the Phi series beyond this point would no longer yield semi-regular intervals. Instead, the intervals would follow the ratio of 1:1.01758 relative to our original intervals, the same ratio that exists between Phi ×6 and Phi ÷7.

This process would continue for another 13 steps, after which the intervals would be created in the 1 : 1.01758 ratio in the opposing direction from the original set, resulting in an overall ratio of approximately 1 : 1.0758 on either side. From this, we can hypothesize that within the context of a 2 : 1 octave framework of simultaneous divisions and multiplications, Phi progresses through cycles of 13 and 3, and is therefore not an arbitrary reference point from a mathematical perspective. Beyond three cycles of 13, the structure would begin to break down into a finer series of smaller divisions.