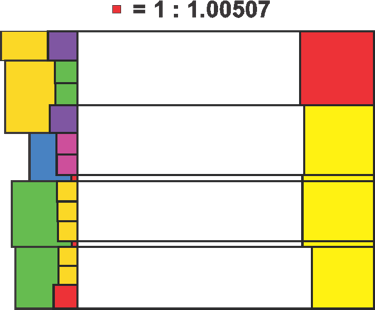

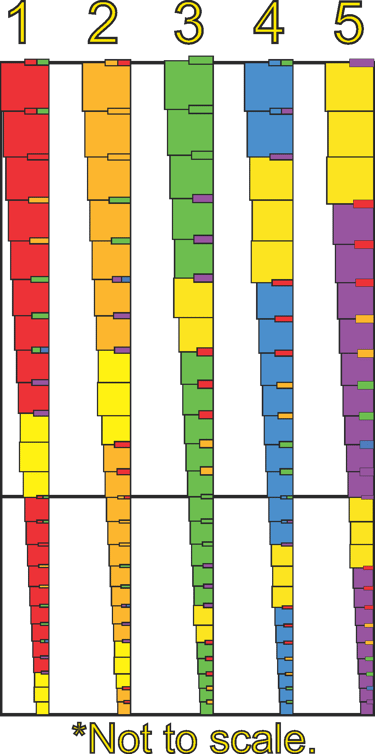

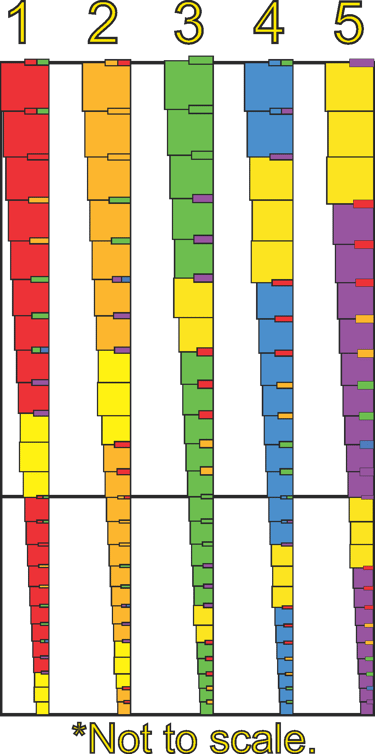

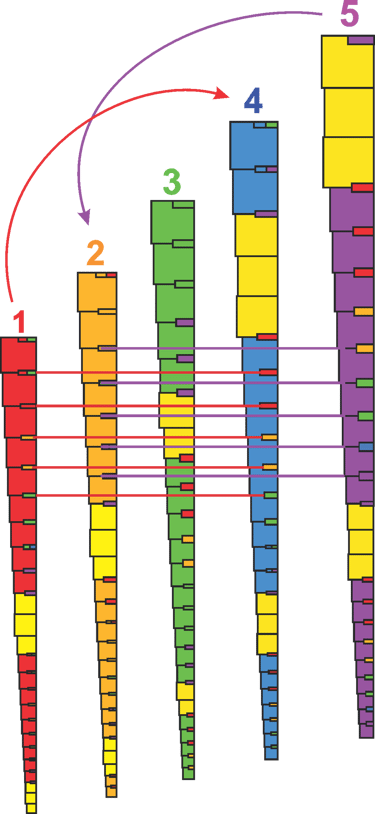

By now, we have completed five iterations of our first basic structure, which together yield the same values we would reach by simply continuing to multiply and divide the original octaves by Phi in three cycles of 13. In the following process, we can demonstrate how these five iterations correspond to particular Phi-harmonic nodes and points of interrelation within the overall structure.

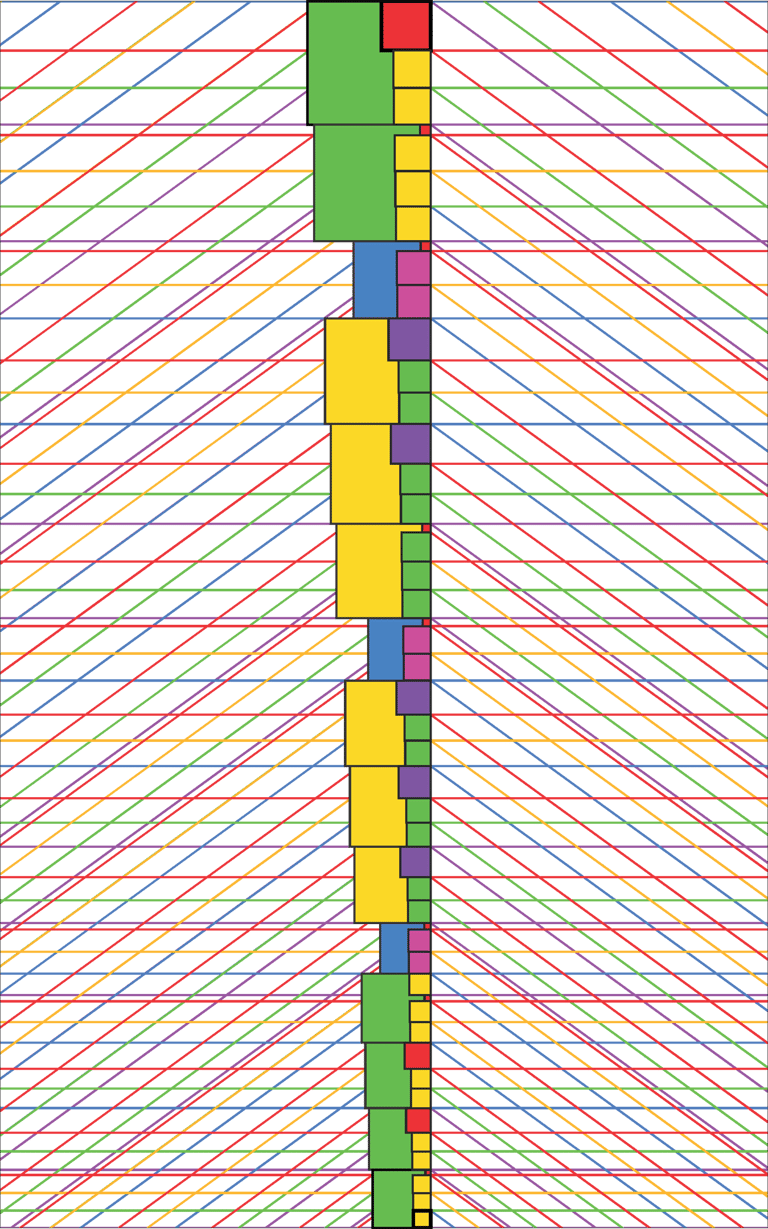

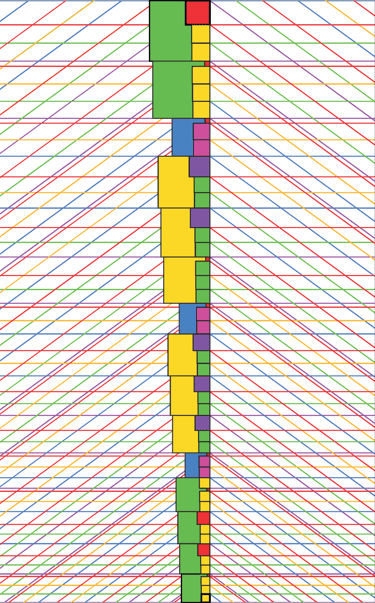

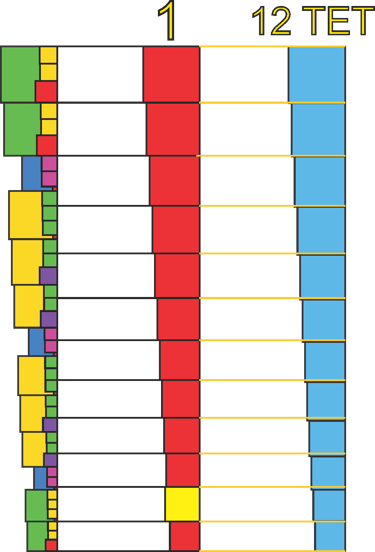

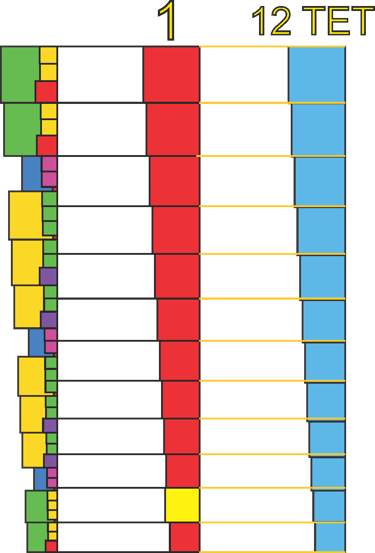

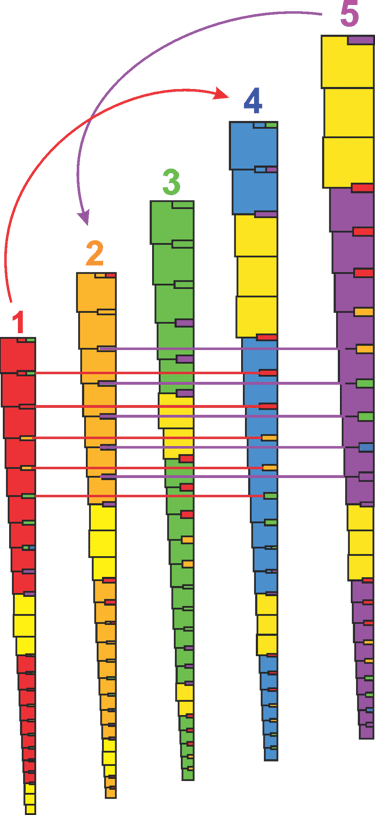

The next step is to overlay the five iterations and highlight the intervals naturally created by each, relative to its own iteration. By examining the base intervals of one iteration in the context of the interpenetrating intervals from the other four iterations, we generate a series of sub-intervals from the perspective of each unique iteration.

By Cree M.J.

Phionic Geometry

The Connected Whole

Now we can see a complex relationship of intervals across the 5 iterations. Though the literal values of each interval remains constant , relative to each set, it has a different framework to work with.

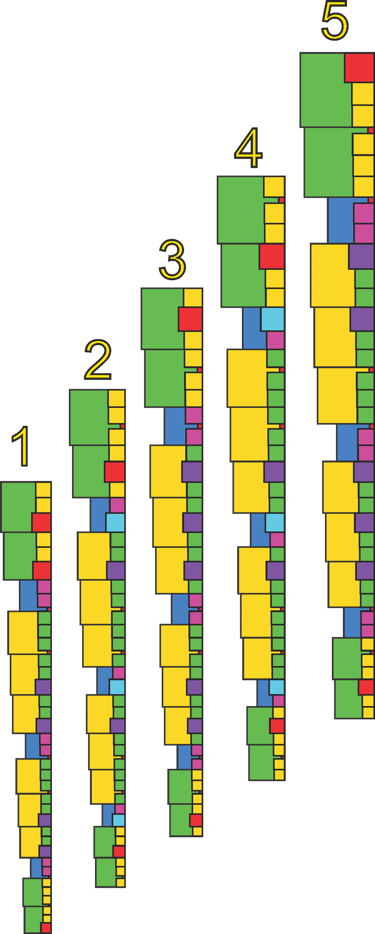

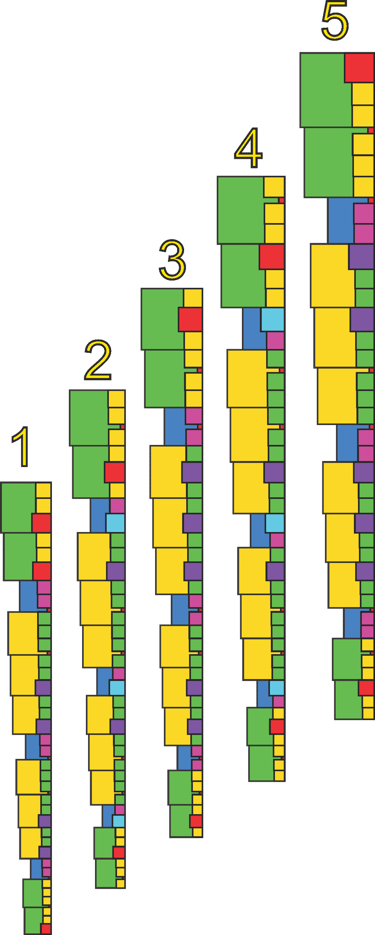

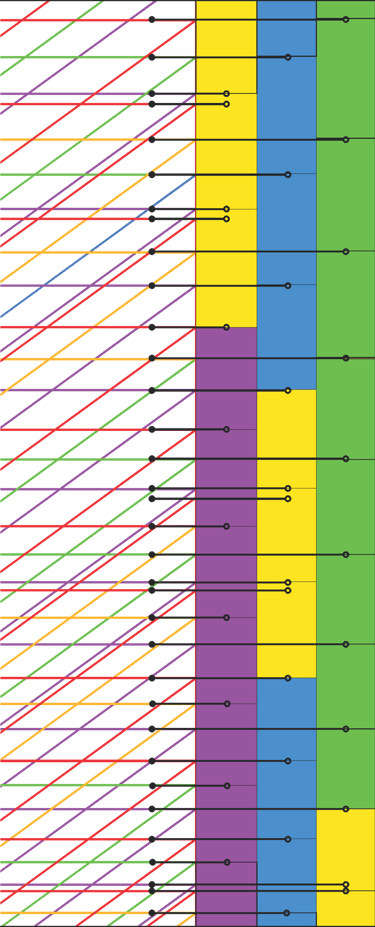

There is now only one final step to reveal the structure. We take the musically familiar 1:1.059 ratio present within the iterations and use it to construct an entirely new scale, assigning each note to the closest available interval within the existing iteration values.

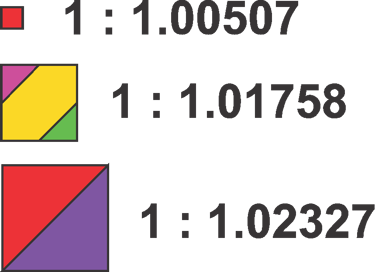

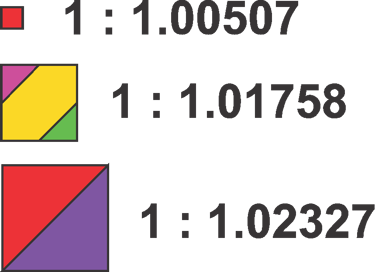

Because our interval is slightly less than the 12th root of 2 (1:1.05946), the standard interval of equal temperament, a small discrepancy remains, and the 1:1.059 ratio falls just short of completing the octave. This new interval is not an unfortunate inconsistency; rather, it reflects the interrelations of the iterations, the Phi organizing principle, and the phase-in/phase-out points between iterations. This interval may be referred to as the “Bridge Interval.”

Comparing the five Phionic scales, we see that the first is equivalent to the fourth, and the second is equivalent to the fifth, effectively reducing the structure to three unique scales. The central scale is uniquely stable, with only two possible Bridge Interval locations. When we compare these three scales to the five iterations, we find that every interval has been efficiently assigned without overlap, forming a series of consonant scales determined solely by the Phi organizing mechanism.

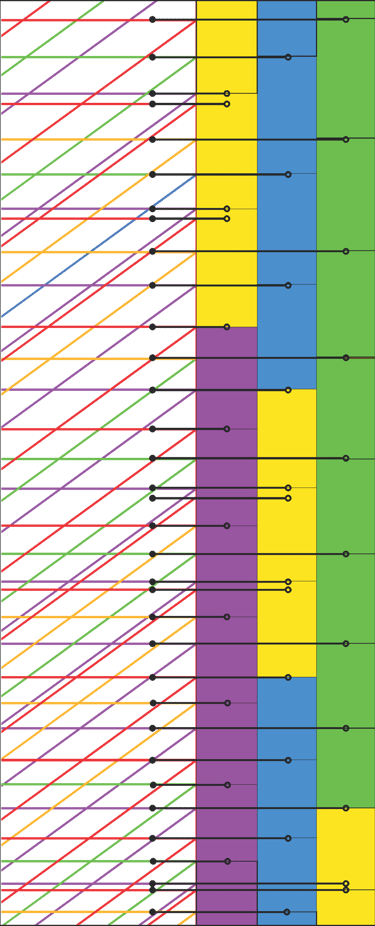

This completes the Phionic structure—a system that can be understood as the musically consonant harmonic nodes of a series of golden ratio-based octaves. It describes not just a single scale, but a unified field of interwoven scales.

Now that we have identified the core of the Phionic Series, we can expand the scale to reveal an endless chart of possible Phi-Octave relationships. This series is intended for musicians interested in exploring tuning based on the golden ratio, offering a geometric, poly-scale, microtonal framework of intervals.