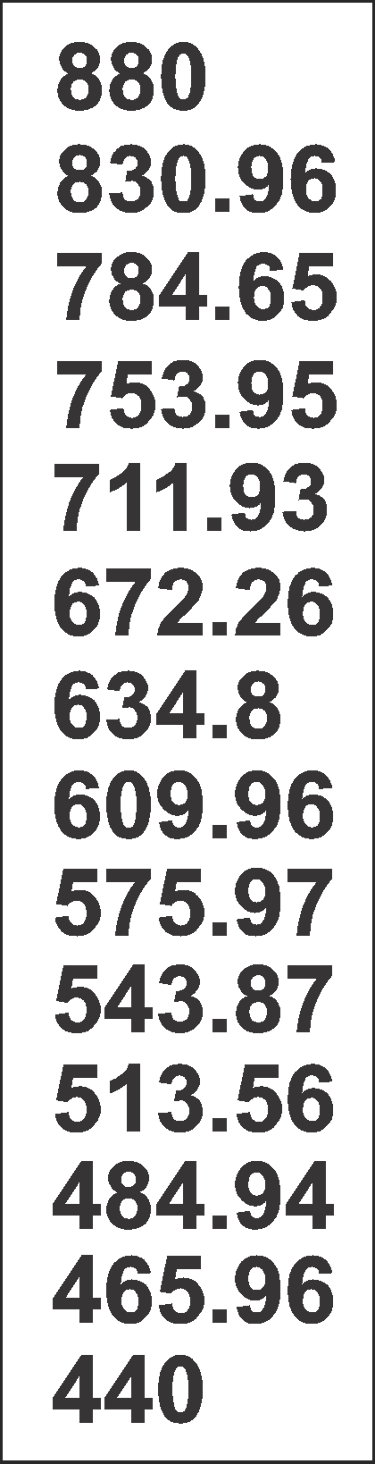

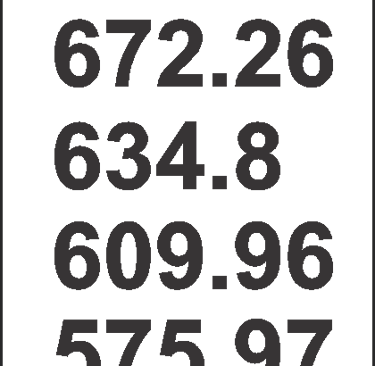

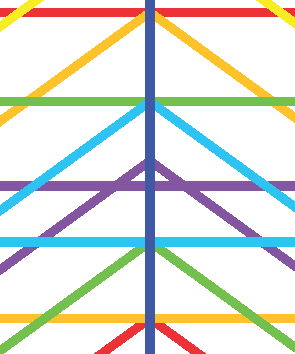

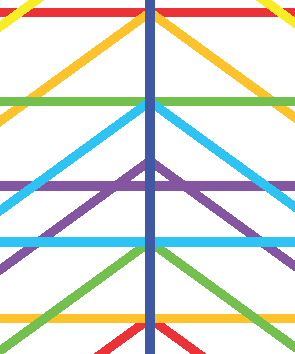

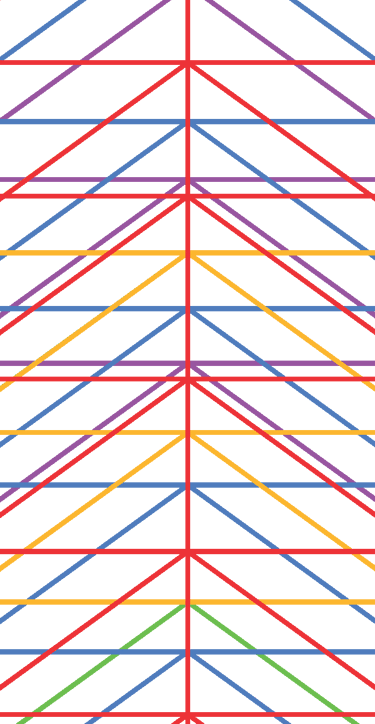

If we now highlight these thirteen intervals, a rather interesting pattern emerges. A block of four intervals bridges the octave, and within this block, we can see two smaller blocks of three intervals each, separated by three even smaller intervals. The ratio of the larger intervals is approximately 1:1.05901, which is extremely close to the 1:1.059463 ratio of intervals in equal temperament. The smaller intervals have a ratio of approximately 1:1.0407.

By Cree M.J.

Phionic Geometry

Intervals and Iterations

These intervals can also be thought of as approximate fractions of Phi, though not exact, since they result from complex overlapping within the structure. The 1:1.059 interval roughly corresponds to Φ¹⁄⁹, while the 1:1.0407 interval is approximately equal to Φ¹⁄¹²

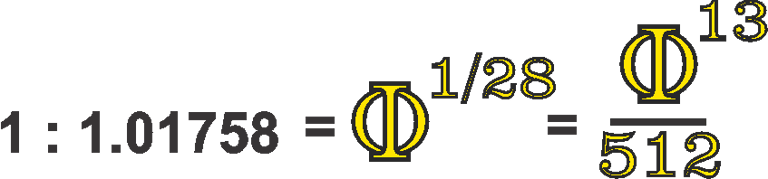

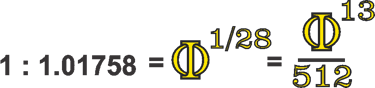

By examining the intervals between the Phi ÷7 and Phi ×6 points, we can see that the 1:1.01758 ratio represents the exact difference between these two sets of ratios. It functions almost like an intermediary overlap for other intervals embedded within the structure, effectively serving as a bridge between them.

Assigning these values to Hertz and playing them produces a scale that conveys some sense of harmony and pleasant chords, yet retains enough dissonance to feel slightly rough around the edges.

To move beyond this point, we need to “tune” our scale. The next step in refining the tuning of these frequencies and deepening our understanding of Phi is recognizing that Phi does not form a closed system; rather, it spirals infinitely through the spectrum of numerical relationships.

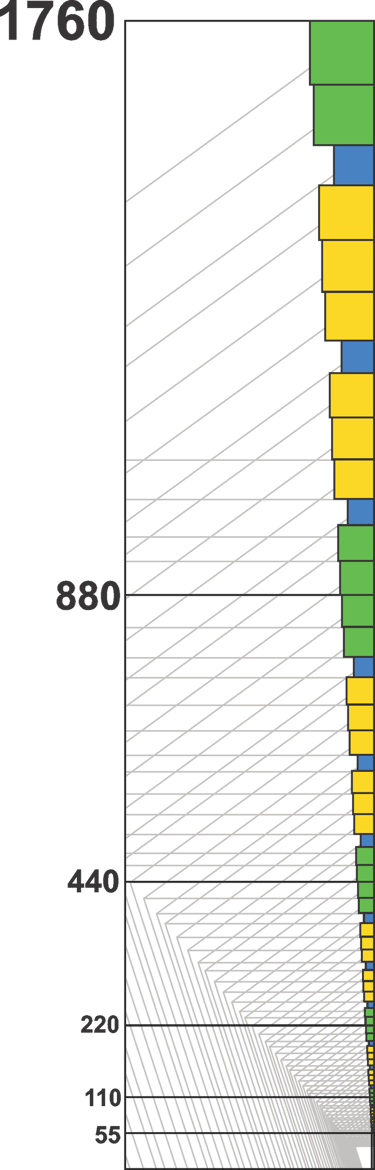

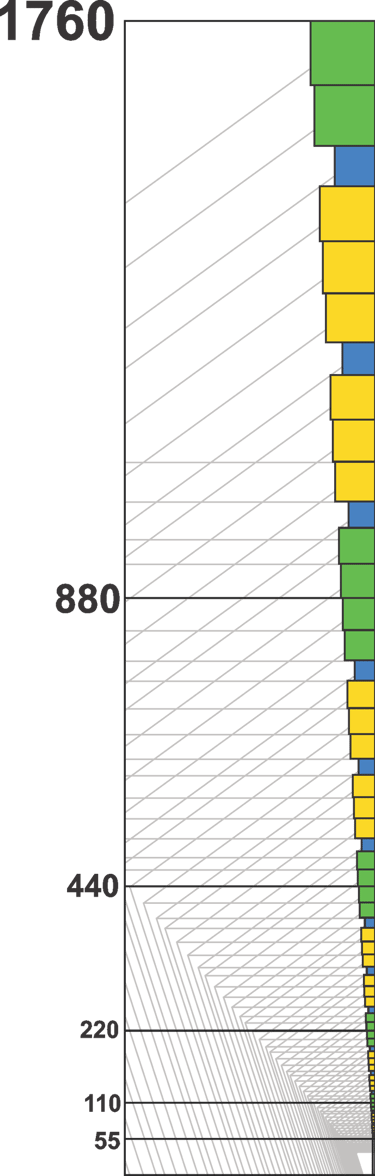

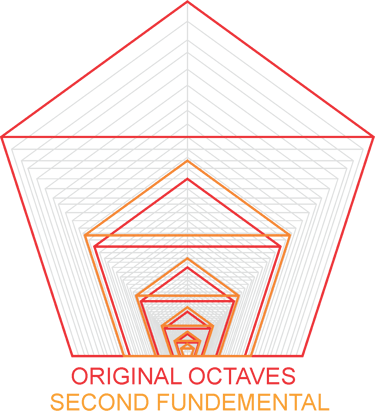

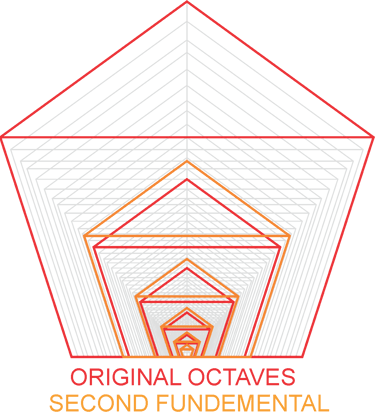

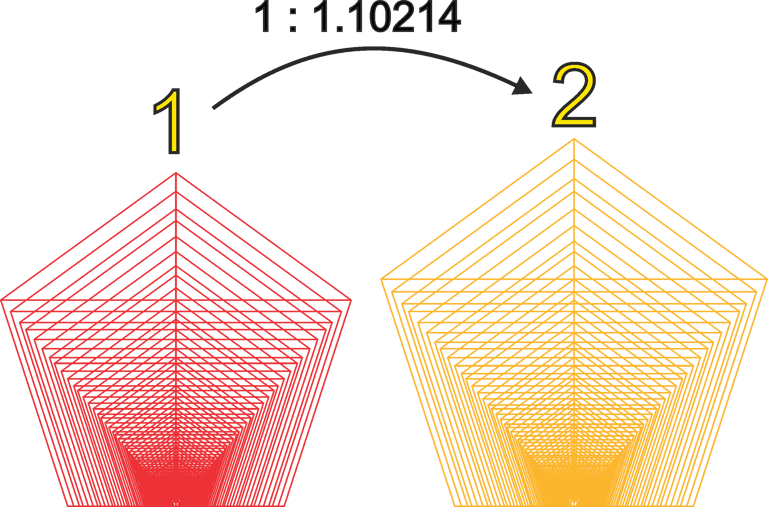

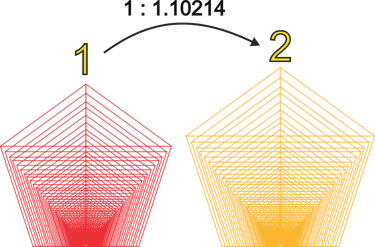

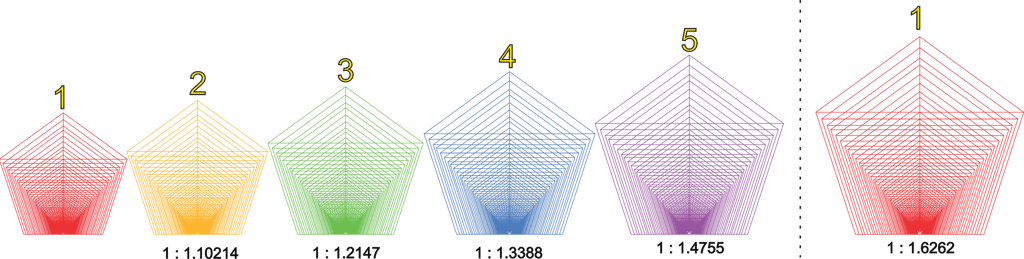

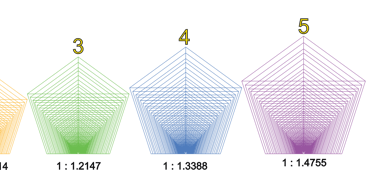

While this additional set alone provides a series of alternative values that can be used musically, in its current state it appears somewhat arbitrary, and the exact relationships are not yet apparent. We can, however, get a hint of how many times to repeat this process by examining the specific ratio of these scales, 1:1.102141, which is approximately 1/5 of Phi. To complete a full Phi cycle, we aim to create 5/5 of Phi, which means we will simply repeat the structure three more times.

The iterations stop just short of the approximate 1.6262 Phi interval, as we must include the first set in the calculation. The value 1.6262, which is 1.618 × 1.00507, will become meaningful later. This 1.6262 interval actually marks the beginning of yet another series of five iterations, or a new Phi-Cycle. Similarly, the beginning of our current set corresponds roughly to the Phi ratio of the preceding Phi-Cycle. It is important to note that iterations and Phi-Cycles are distinct and do not arbitrarily overlap; when one Phi-Cycle is clearly defined, the others fit into place systematically.

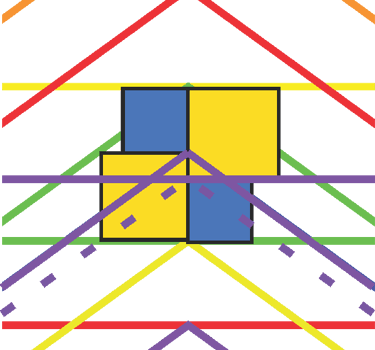

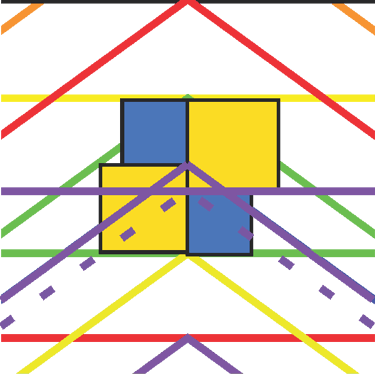

After completing the five iterations, we now have the basic framework from which to derive our musical structure. This Phi-Cycle of five iterations can be considered the “skeleton” of the structure. Several observations at this point underscore the mathematical significance of this construction, beyond abstract interpretation:

By analyzing the intervals closely, we can see that, for the same reason we stopped our fundamental structure at six Phi steps, the first irregular intervals appear only through the combination of the first and last iterations—between the purple (first) and red (last) lines. Here, Phi begins to “put its foot in the door” of the next series of values rather than rounding itself neatly. In fact, these intervals are exactly the same as those obtained by continuing to multiply and divide by Phi from the original octaves in three cycles of 13, as noted on the “Fundamental Structure” page.

This alternative route requires more iterations because only half of each iteration’s values are unique, while the other half overlap with the previous iteration. One might interpret this as iterations being woven and interconnected in a unique way, offering a distinct advantage for understanding the structure from this perspective.

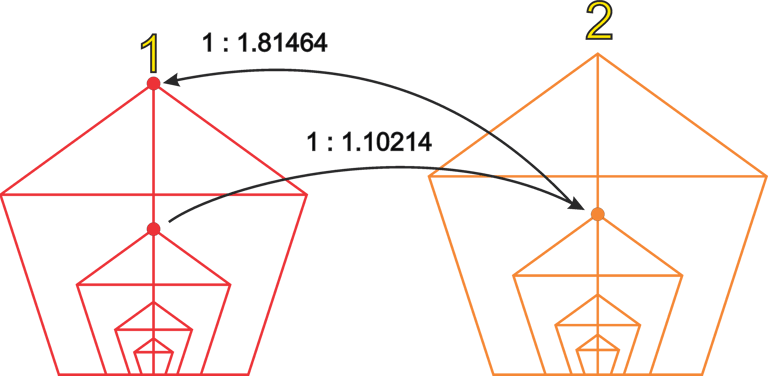

Another point to note is how the iterations are constructed. We create the next iteration’s fundamental octave values starting from the Phi ÷7 mark, approximately 1:1.102141 relative to the original octave. If, instead, we start from the Phi ×7 mark and build the fundamental octaves from that point, the resulting octaves are in a ratio of approximately 1:1.81464 relative to the original octaves.

The iteration generated from Phi ×7 produces values exactly equal to those of the previous iteration, but shifted up by one octave. We can identify these specific points within the overlapping Phi structure: the number 1.102141 is approximately equal to 32 / Φ⁷, and 1.81464 is approximately equal to Φ⁷ / 16. Here, the numbers 16 and 32 correspond to 5 and 6 octaves in the octave series.

Thus, we can observe a balance: Phi ÷7 defines the iterations in one direction, while Phi ×7 defines them in the opposite direction.